|

|

|

|

| By Kimberley Rew |

Robyn

Hitchcock arrived in the medium-sized college town of

Cambridge, England in 1975 to look for musicians for

his band—not an obvious choice of location as a hotbed

of talent but none of this would apply if he hadn't.

I first heard him at some weekly informal musical get-togethers

at the Great Northern Hotel run by a man called Sunshine

Joe, with a backing band he later described as 'people

who were living in my house'. Robyn wore black leather

trousers and jacket, long hair and beard, and either

glowered at the audience or, then as now, launched into

lightningly impromptu song introductions which took

the subject matter on a season ticket to Unexpectedsville. |

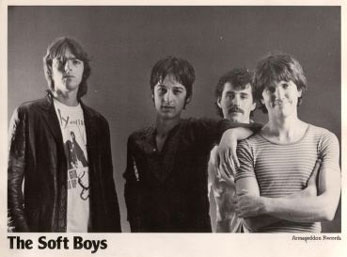

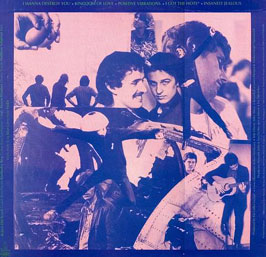

| Morris

Windsor, Kimberley Rew, Robyn Hitchcock, Matthew Seligman |

|

| |

|

| At

the time I was renting a room in a terraced house

whose basement contained Spaceward recording studio.

Robyn arrived and recorded and we met in the kitchen

where he stubbed his fag on the lino and was rebuked

by recording engineer Mike Kemp. Mike subsequently

invented the 'Sadie' hard disk recorder and retired

to the Algarve. Morris Windsor, Rob Lamb (and original

Waves singer Rob Kelly) were in local rock outfit

Mad Hatter whom I heard at a cricket pavilion on

one of those balmy summer night college shindigs.

Rob and Morris went on to form Sheboygan (which

I thought for a long time was a quote from Surfin'

USA, but then found was a generic name for 'Nowheresville')

and discovered pub-rock. The next year, 1976, in

pursuit of a 'white soul' style, they teamed up

with Robyn and Andy Metcalfe to form Dennis and

the Experts and began to rehearse in Robyn's front

room. Uneasy about the way things were shaping,

in December Rob quit (subsequently forming the respected

Ducks on the Wall, whose Adrian 'Hots' Foster gave

us the phrase 'I've got the hots for you'). Except

Robyn was in bed at the time so he had to shout

his resignation thru the keyhole. |

|

|

| |

|

Dennis

and the Experts were booked that month for a university

Christmas ball—recruiting Alan Davies on guitar, Robyn

arrived at the venue, which being an educational institution

had a blackboard, that night being used to list the evening's

musical program. Erasing 'Dennis and the Experts', he

chalked in 'The Soft Boys'. Thus were they born. Now began

the group's truly formative year. All the distinctive

musical ingredients were brewed—incisive lyrics, unexpected

twists (at least few expected twists), the twin guitar

attack. There was a vague feeling among the local musos

that it wasn't 'proper' music—proper music at the time

was more a swamp of 'tasteful' licks at the pinnacle of

which, if swamps have pinnacles, was Steely Dan. |

Nobody

of course ever actually could play like Steely Dan, but

that distant peak was always in view. Certainly it was

hard to hear the subtleties of the Soft Boys through the

group's two 4x12 WEM columns. That all changed with the

appearance of the EP Give it to the Soft Boys on

Raw Records, run by local entrepreneur Lee Wood, that

summer of 1977. There was 'Wading thru a Ventilator' in

all its glory, lyrics originally aimed at Robyn's neighbour

Vyrna Cole now turned in upon himself, the rising guitars

of the middle eight raising hair on arms. |

|

| |

|

|

The

Soft Boys began to get second-on-the-bill gigs in London,

supporting among others the Pirates, Elvis Costello, and

the Vibrators, where they met long-term producer Pat Collier.

I joined in January 1978, having baby-sat and sat in the

previous month. We signed to the short-lived Radar Records,

who had Costello and Nick Lowe and were thus considered

the last word in cool. (This is the only time in my life

I have  ever

been cool and then only by association). We opened for

the Damned—the only time in my life I have ever attended

a punk gig. Radar financed an album to be made over two

weeks at the residential Rockfield studios on the Welsh

border. But the coolness was already returning to room

temperature and the album was mothballed, followed shortly

by the rest of the record company. ever

been cool and then only by association). We opened for

the Damned—the only time in my life I have ever attended

a punk gig. Radar financed an album to be made over two

weeks at the residential Rockfield studios on the Welsh

border. But the coolness was already returning to room

temperature and the album was mothballed, followed shortly

by the rest of the record company. |

|

|

|

|

| This

was the time when the nation limped half-heartedly

after punk—it was not the glittering golden age

that it was later labelled. Gigs in Swansea, Leeds

and elsewhere were attended by small numbers of

punks who had a miserable time (but if you were

a punk that of course meant you had a great time

because the object was to be miserable). It was

also the time of Supertramp's 'Logical Song' and

Dire Straits' 'Sultans of Swing', which were played

incessantly at ear-melt volume in these joints,

and which I never want to hear again. Bands such

as Squeeze and the Police, who had been 50p on

the door at the Hope and Anchor when we were charging

75p, whizzed past at 100mph. |

|

|

| |

|

| Robyn

put up the cash to record A Can of Bees independently

at Spaceward on his own Two Crabs label. After the

album's quiet reception and some more recording

of songs like 'When I Was a Kid' and 'The Asking

Tree', Andy left to team up with Telephone Bill

and the Smooth Operators in summer 1979. Also taking

the opportunity to quit were harmonica player Jim

Melton, sound engineer Ivan Carling, and lighting

man Mungo Carstairs. This left the skeleton of Hitchcock,

Windsor, Rew and new bass player Matthew Seligman.

Matthew was a respected local player—my girlfriend

Lee used to listen with her head in his bass cabinet.

Oddly at the time no one could drive. I passed my

driving test and the day after ferried the gear

down to London's Rock Garden (the first place I

saw the phrase 'coffee-table album') in a borrowed

Volkswagen van. The handbrake didn't work but if

you took your foot off the gas it stalled. So if

you stopped on a hill you had to either balance

the van on the clutch or theoretically stay there

for ever. |

|

| |

|

|

| We

returned to Spaceward and recorded 'I've got the

Hots', 'He's a Reptile', 'Song Number Four' and

'You'll Have to Go Sideways'. This last consisted

simply of a guitar riff repeated over and over for

three minutes. The studio owned a Mini Moog synthesiser,

then costing some £600 (a vintage Stratocaster

was £300). I prevailed on engineer Mike Kemp

to let me plaster the multitrack with one-finger

Moog (they'd just gone 16-track). This was the first

and probably last time anything of the sort was

attempted. The Cambridge City Rowing Club Boathouse

now became available for band rehearsals—the second

Cambridge outfit to use it were the Dolly Mixtures,

who later achieved fame backing Captain Sensible.

It was an unloved building, curtains terminally

adrift from their plastic rails, sandwiched between

much swankier structures belonging to the historic

colleges. Day after day we would meet there to work

on the songs that eventually became the Underwater

Moonlight album, plus efforts such as Goodbye

Steve (whose words changed completely with every

rendition), which were dug up for the 2001 bonus And How It Got There disk, before retiring

to Hambis' cafe where egg and chips were 40p. Hambis'

house rules were No Schoolboys and No Chips Alone.

A local character dubbed The Face of Death (who

had inspired that song and was now indeed dead)

had redecorated the joint and it was thought, rather

cruelly, that one corner where the dado plunged

alarmingly floorwards was where he had actually

expired. |

|

|

|

|

As

the new decade began we ventured to Pat Collier's

4-track Alaska studios, located in a dripping

tunnel near London's Waterloo station—still there,

with the same cigarette burns on the same sofa.

(It's long since gone 24-track, stopped dripping,

and has been home to many hit recordings). This

was a one-man operation in the truest sense, i.e.

there were other employees but they didn't actually

do anything. Pat would frequently record the band

in filthy overalls (Pat, not the band), having

just installed a false ceiling or something. A

welcome feature was the La Ronde across the street

where one could get nourishing bread pudding—this

was later demolished to make way for the Jubilee

Line tube extension (the La Ronde not the bread

pudding). We recorded 'Queen of Eyes', 'Kingdom

of Love', and 'I Wanna Destroy You' (please note

this last is a parody of punk, not punk itself). |

|

|

|

|

The

first stirring of suspicion of the group's worth

independently of the media hooha of two years

previously came with the appearance in our career

of the tiny Armageddon label, who put out the Kingdom of Love EP, which crept to about

25 in the New Musical Express 'alternative' charts.

Increasing our crew to one with Howie Gilbert,

we embarked on a tour of Scotland, staying in

a 'family room' with five beds in an Edinburgh

hotel. This was connected by intercom to the front

desk. Being asked in the morning if there were

still five of us, Robyn, whose bed was nearest

the intercom, replied 'no, one of us has had a

baby'. It was felt that the forthcoming album

needed technical beefing and we switched to the

8-track James Morgan studio. It was in James Morgan's

house, in a street in a South London neighbourhood

which to this day I have never been able to find

again. Here we put down 'Insanely Jealous', 'Underwater

Moonlight', 'Positive Vibrations' etc. The

first stirring of suspicion of the group's worth

independently of the media hooha of two years

previously came with the appearance in our career

of the tiny Armageddon label, who put out the Kingdom of Love EP, which crept to about

25 in the New Musical Express 'alternative' charts.

Increasing our crew to one with Howie Gilbert,

we embarked on a tour of Scotland, staying in

a 'family room' with five beds in an Edinburgh

hotel. This was connected by intercom to the front

desk. Being asked in the morning if there were

still five of us, Robyn, whose bed was nearest

the intercom, replied 'no, one of us has had a

baby'. It was felt that the forthcoming album

needed technical beefing and we switched to the

8-track James Morgan studio. It was in James Morgan's

house, in a street in a South London neighbourhood

which to this day I have never been able to find

again. Here we put down 'Insanely Jealous', 'Underwater

Moonlight', 'Positive Vibrations' etc. |

|

|

|

|

| The Underwater Moonlight album appeared

in summer 1980. By this time the band had

already moved to London and Robyn had recorded

'The Man Who Invented Himself'. Things were

changing. 'Only the Stones Remain' was probably

our last solid studio effort, eventually

appearing on the posthumous half-live Two

Halves For The Price Of One budget-priced

album, but we never really found a decent

place to rehearse in North London. One attempt

was in the basement of a house occupied

by an emigré Scottish heavy metal band.

This, like that hotel room, was connected

by intercom to the living room upstairs.

Morris played his usual kit but, during

a break, was tempted over to the heavy band's

kit because it had 14 million tom-toms.

He immediately received a protest on the

intercom from an irate Scottish drummer. |

|

|

|

The

group was however yet to embark on its biggest single

adventure—a trip to New York, staying at the Iroquois

on 44th Street, playing at such places as the Danceteria,

the Mudd Club and Maxwell's in Hoboken, the only place

in the world where I've appeared with the old Soft Boys,

the new Soft Boys, Katrina and the Waves, Robyn Hitchcock

solo, and myself solo. We returned, as you often do

from New York, at six in the morning, somehow bringing

a New York band, the Method Actors, with us, sitting

opposite them on the rattling tube. Once through the

front door I retired to bed due to lack of funds. |

|

|

| |

The

group's last show was at second-league pub venue the

Golden Lion, Fulham, London in February 1981. Unknown

to us we were already 'influencing' some younger American

musicians. Many adventures followed over the next nineteen

years but what mainly happened to the Soft Boys was

that the Underwater Moonlight album became 'legendary',

reappearing on Rykodisc in 1992 with a host of extra

tracks. Its subsequent unavailability perhaps fueled

the mystique until 2001 when Matador picked up the baton.

Robyn was on his second post- The

group's last show was at second-league pub venue the

Golden Lion, Fulham, London in February 1981. Unknown

to us we were already 'influencing' some younger American

musicians. Many adventures followed over the next nineteen

years but what mainly happened to the Soft Boys was

that the Underwater Moonlight album became 'legendary',

reappearing on Rykodisc in 1992 with a host of extra

tracks. Its subsequent unavailability perhaps fueled

the mystique until 2001 when Matador picked up the baton.

Robyn was on his second post- Egyptians

album, Morris was working with the Gliders, Matthew

was finishing the first Snail offering, and I had completed

eighteen years with Katrina and the Waves. Several reunions

happened at the Feghorn pub in Central London's last

surviving neighbourhood of Clekenwell, topped off by

an appearance at Matthew's wedding reception in Kensal

Green. It felt like the next booking the week after

the Golden Lion. Kensal Green saw the debut of 'Sudden

Town' and it soon became clear that Hitchcock was not

the man simply to dust off relics, but always thinking

in terms of the next new song. First, however, came

the picking up of the transatlantic thread—a month in

Spring 2001 across the USA, the natural extension to

the 1980 New York trip, culminating at San Francisco's

Fillmore. Egyptians

album, Morris was working with the Gliders, Matthew

was finishing the first Snail offering, and I had completed

eighteen years with Katrina and the Waves. Several reunions

happened at the Feghorn pub in Central London's last

surviving neighbourhood of Clekenwell, topped off by

an appearance at Matthew's wedding reception in Kensal

Green. It felt like the next booking the week after

the Golden Lion. Kensal Green saw the debut of 'Sudden

Town' and it soon became clear that Hitchcock was not

the man simply to dust off relics, but always thinking

in terms of the next new song. First, however, came

the picking up of the transatlantic thread—a month in

Spring 2001 across the USA, the natural extension to

the 1980 New York trip, culminating at San Francisco's

Fillmore. |

|

|

| The

group reconvened in Pat Collier's new Gravity Shack

studios in South London to record a contribution

to a Tribute to Paul McCartney album, which developed

into the Nextdoorland album sessions. The

leftover songs were assigned to a CD EP called Side

Three. The bread puddings were replaced by cheese

and bean wraps and sushi, which always looked to

me suspiciously like party nibbles. Punk metal dirges

from the next studio were replaced by the dim thud

of electronic beats through the floor from a warren

of 'programming rooms'. To keep in shape there were

gigs at Evershot village hall in Dorset, the Victoria

and Albert museum (strangely) and, very satisyingly,

opening for the Pretty Things on the South Bank,

including a version of 'Astronomy Domine' with stereo

Barrett guitar from Robyn and Pretty Things' special

guest Dave Gilmour. At the time of writing, September

2002, the Soft Boys are about to embark on a second

American tour to celebrate Nextdoorland—'not bad

for a reunion album', commented Nigel Cross. Happy

listening and thank you all for helping to make

the Soft Boys a major experience of my life. |

|

|

|

|

|

|